Drugs: An Ever-Evolving Problem In Kosciusko And Beyond

Dealing with illegal drugs in northern Indiana is a bit like a game of Whack-A-Mole.

If it’s not one drug, it’s another.

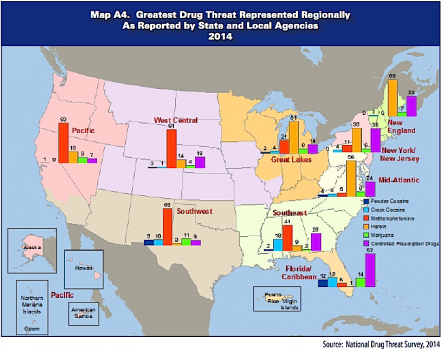

Due to proximity to Lake Michigan and a number of highway systems, northern Indiana is a drug transportation and distribution area, according to the Drug Enforcement Agency. Ink Free News has gotten some reports that cocaine is on the rise in northern Indiana.

Cocaine Making A Comeback?

Some recent busts have seen the seizure of 100 kilograms of cocaine in Fort Wayne and 35 kilograms of cocaine in Indianapolis in the last few months. However, the Kosciusko County Sheriff’s Department reported that it has not seen any significant spikes in cocaine-related incidents locally. There have been some minor arrests in Kosciusko County in 2015, namely Jorge Castro and Daniel Vasquez, who were arrested for dealing cocaine in March. Castro was charged with possession of more than 10 grams, merely a fraction of the volume found in Fort Wayne.

Meth, Pills Still Kosciusko’s Biggest Problem

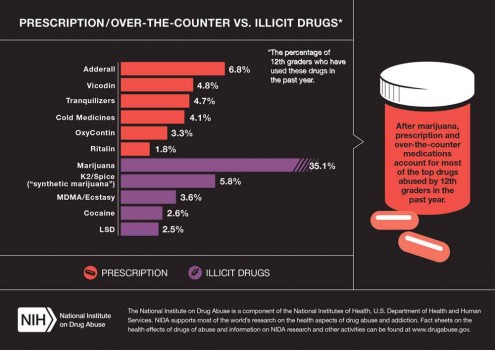

KCSD First Sgt. Chad Hill said meth remains the highest drug-related issue in Kosciusko County, followed closely by prescription drug abuse. DEA data does indicate that abuse of prescription medication remains a persistent problem throughout the nation, and, alarmingly, prescription pain killers are gaining on marijuana as the first drug abused by first-time users.

On the other side of the state, an HIV epidemic in Scott County exploded as a result of intravenous abuse of Opana, a prescription pain killer. A recent update from the state health department shows 162 confirmed cases of HIV, and the Scott County Needle Exchange program had taken in more than 17,000 needles and provided 18,713 clean needles – that’s in a county of approximately 25,000 people.

Heroin On The Rise

Hill did report an increase in heroin-related incidents in the area. This correlates with DEA data that shows an increase in heroin seizures, with numbers nearly doubling since 2009.

Hill did report an increase in heroin-related incidents in the area. This correlates with DEA data that shows an increase in heroin seizures, with numbers nearly doubling since 2009.

In that bust in Indy back in March, officials also seized 35 kilograms of heroin, enough to give 1/8 of the city a dose. And earlier this month, Fort Wayne Police Department was investigating three deaths, all occurring within a 24-hour period, which were believed to be heroin related. The incidents forced FWPD and the Allen County Coroner to issue a release warning of extremely powerful heroin on the street.

This uptick in heroin seems to correlate with prescription drugs becoming less user-friendly. With prescription pills, especially opiates, going up in price, becoming more difficult to obtain, and even – like in the case of OxyContin – being reformulated to prevent abuse, a number of abusers have turned to heroin as a cheaper, more attainable fix.

Last year, “Rolling Stone” ran an expose, “The New Face Of Heroin,” addressing the rise of heroin in rural America. Author David Amsden reported that as of April 2014, 77 percent of recent heroin users said they had switched to the drug after first trying prescription pain killers.  And though Amsden’s article focused on rural Vermont, it noted that the crackdown on prescription meds opened up an opportunity for Mexican and South American drug cartels to push heroin and cocaine all over the U.S.

And though Amsden’s article focused on rural Vermont, it noted that the crackdown on prescription meds opened up an opportunity for Mexican and South American drug cartels to push heroin and cocaine all over the U.S.

Synthetic drugs, like “Spice” or “K2” and bath salts, are still around. The American Association of Poison Control Centers reported a decline in exposure calls between 2011 and 2013, but the National Institute of Drug Abuse reports, as of 2014, that synthetic cannabinoids are the second most-used illicit drug among 12th graders.

Which brings us back around to that Whack-A-Mole metaphor. If an Oxy addict can’t get her pills, she can probably score some dope. If a college student can’t pick up some weed, he can substitute with spice. If KCSD busts a meth lab, more will pop up.

So what’s the solution? Unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to be a hard and fast answer. In Kosciusko County, the Alcohol and Drug Program and Drug Court are beginning to shift the way drug cases are handled, moving away from penalization and toward rehabilitation. D.A.R.E. programs are offered in area schools to educate young students about the perils of drug abuse.

Education remains a crucial piece of the puzzle. Policy reform based on founded scientific data is another. No longer treating nonviolent drug offenders as hardened criminals is another. Perhaps the proliferation of hardcore drugs like meth and heroin in America’s small towns, like those that dot the landscape of northern Indiana, will be the impetus to reform drug policies and practices.